By Codi Darnell

January 25, 2022

Deciding to seek care at an emergency department isn’t usually a decision people make lightly. Who wants to sit around for hours in a lineup of assorted symptoms, drowning in the smells of bodily fluids vaguely masked by latex and isopropyl alcohol? Not most people. But heading to the hospital when you have a previous existing condition, like a spinal cord injury, can make the process more complicated.

Deciding to seek care at an emergency department isn’t usually a decision people make lightly. Who wants to sit around for hours in a lineup of assorted symptoms, drowning in the smells of bodily fluids vaguely masked by latex and isopropyl alcohol? Not most people. But heading to the hospital when you have a previous existing condition, like a spinal cord injury, can make the process more complicated.

Because most practitioners don’t have much experience treating people with a spinal cord injury, their knowledge of the condition is limited which can cause problems when it comes to diagnosing and caring for the patient. While the patient’s current complaint may not be related to the spinal cord injury, the way it presents may be altered because of it. This means there is a need for practitioners to understand the chronic condition while also separating the current complaint.

I recently found myself in an emergency room with aseptic meningitis (a rare reaction to an antibiotic). Having been sent to the hospital by my doctor, I already knew the likely diagnosis and that it had nothing to do with my spinal cord injury.

So when the triage nurse paused in the midst of my assessment to get the backstory of my spinal cord injury, I was irritated. Because, while the injury itself gives context to my overall health, the story is irrelevant. The short version seemed to appease her curiosity and she shook her head and said, “Oh, how tragic.”

So when the triage nurse paused in the midst of my assessment to get the backstory of my spinal cord injury, I was irritated. Because, while the injury itself gives context to my overall health, the story is irrelevant. The short version seemed to appease her curiosity and she shook her head and said, “Oh, how tragic.”

“It’s really fine. I’m actually just concerned about the headache right now,” I said while trying to keep the frustration out of my voice.

I was admitted for three days. I am a non-weight bearing full-time wheelchair user with no sensation below my belly button, yet I had doctors and nurses ask me to stand up, and inquired about pain in places I cannot feel – and not just once. I answered the same questions and explained the same aspects of my injury with every new practitioner that came to my bedside. Nothing was noted in my chart, nobody made sure my body was moved to prevent pressure ulcers, and there was little to no awareness as to how my body might need to be treated differently, and seemingly little desire to understand.

Now there is no doubt that hospital staff are busy and stretched thin in many departments, and I have no expectations that nurses and doctors become experts in every chronic condition – that would be unrealistic. But a baseline knowledge of what to expect with certain conditions, and an effort to keep track of that information for other caregivers who work with a patient, would make the acute care experience easier and safer.

Here are five things that staff working in an acute care setting should know about spinal cord injury.

Mobility and Sensation

Mobility and Sensation

A spinal cord injury affects different parts of the body depending on the level and severity or completion. The amount of mobility and sensation a person has is specific to them and their spinal cord injury. Some patients will be non-weight bearing, some may be able to transfer independently, and others may need assistance. Understanding their level of mobility and sensation will help you meet their needs more efficiently.

Bladder and Bowel Function

Spinal cord injury almost always affects bladder and bowel function to varying degrees and most people with a spinal cord injury use alternate methods to void their bladders and bowels. Some people can manage independently and others will require assistance. People with spinal cord injury are also more likely to develop bladder infections so a sterile technique for catheterization should always be used while in a hospital.

Symptoms

The nervous systems of people with spinal cord injury are functionally different and our symptoms don’t always follow the typical pattern. Someone with a spinal cord injury may experience autonomic dysreflexia, increased spasticity, or neuropathic pain in response to all sorts of issues. Our red flags can look different and it is important to find the root cause. Keep in mind that autonomic dysreflexia itself is a medical emergency and needs to be treated immediately.

Skin Health

People with a spinal cord injury are at increased risk for pressure ulcers. Skin checks should be completed daily and a pressure redistribution mattress should be provided. In addition, the patient should be repositioned every two to three hours at minimum to relieve pressure points. Again, some will be able to independently reposition themselves and others will need assistance.

When it Comes to Their Spinal Cord Injury, Your Patient is the Expert

When it Comes to Their Spinal Cord Injury, Your Patient is the Expert

We live with our injury 24 hours a day, seven days a week. It is our existence, and we know the nuances and understand how our body works and reacts. When we come to you, it’s because something is different from our baseline condition. Trust us that when it comes to our spinal cord injury we know what’s up, and what we need from you is to help us understand the reason behind our current complaint.

A Final Note to Patients and Caregivers

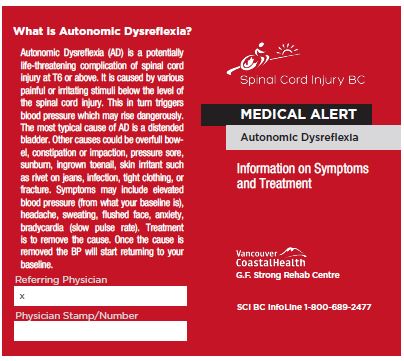

Even when everyone has the best intentions, these conversations can be difficult. Trying to explain the intricacies of a spinal cord injury while dealing with a medical emergency isn’t always possible – just as there isn’t always time to listen and learn. To help with this, Spinal Cord Injury BC has created three wallet cards intended for patients to print out and give to practitioners in acute care. These cards outline basic information regarding bladder care, autonomic dysreflexia, and pressure injury prevention that can help doctors and nurses better understand and care for a patient with a spinal cord injury.

Print these cards out and keep them with you, and if you find yourself in acute care, ask for them to be included in your chart so that everyone has access to the information.

Ultimately, the best thing we can do as patients is advocate for ourselves and what we know about our bodies. As caregivers, we can listen and take note of the information in order to communicate efficiently with other practitioners and provide the best care for the patient. The most important thing to remember is that everyone wants the same outcome – a healthy patient. Sometimes it just requires a little extra cooperation and a willingness to learn.

Thanks to Jocelyn Maffin from Spinal Cord Injury BC for helping me bring this article to light.