By Codi Darnell

January 11, 2022

Recovery from a debilitating illness or injury often revolves around the physical logistics of life – How do you move around? How do you use the bathroom? How do you speak, write, eat? There is no doubt that these physical aspects of life are important, but they are only a piece of the puzzle. The other piece – the emotional piece – is less tangible and tougher to quantify. However, it is equally, if not more, important and it is the soul behind the non-profit organization Stroke Onward.

Recovery from a debilitating illness or injury often revolves around the physical logistics of life – How do you move around? How do you use the bathroom? How do you speak, write, eat? There is no doubt that these physical aspects of life are important, but they are only a piece of the puzzle. The other piece – the emotional piece – is less tangible and tougher to quantify. However, it is equally, if not more, important and it is the soul behind the non-profit organization Stroke Onward.

Debra Meyerson was a tenured professor at Stanford University and a happily married mother of three when, in 2010, she suffered a sudden and debilitating stroke. That stroke left her paralyzed on the right side and without her ability to speak. She worked through her physical rehabilitation for three years to gain back everything she could, but certain residual symptoms meant she could not return to her job at Stanford. She was devastated to give up the job she loved and had to face the question, “Who am I now?”

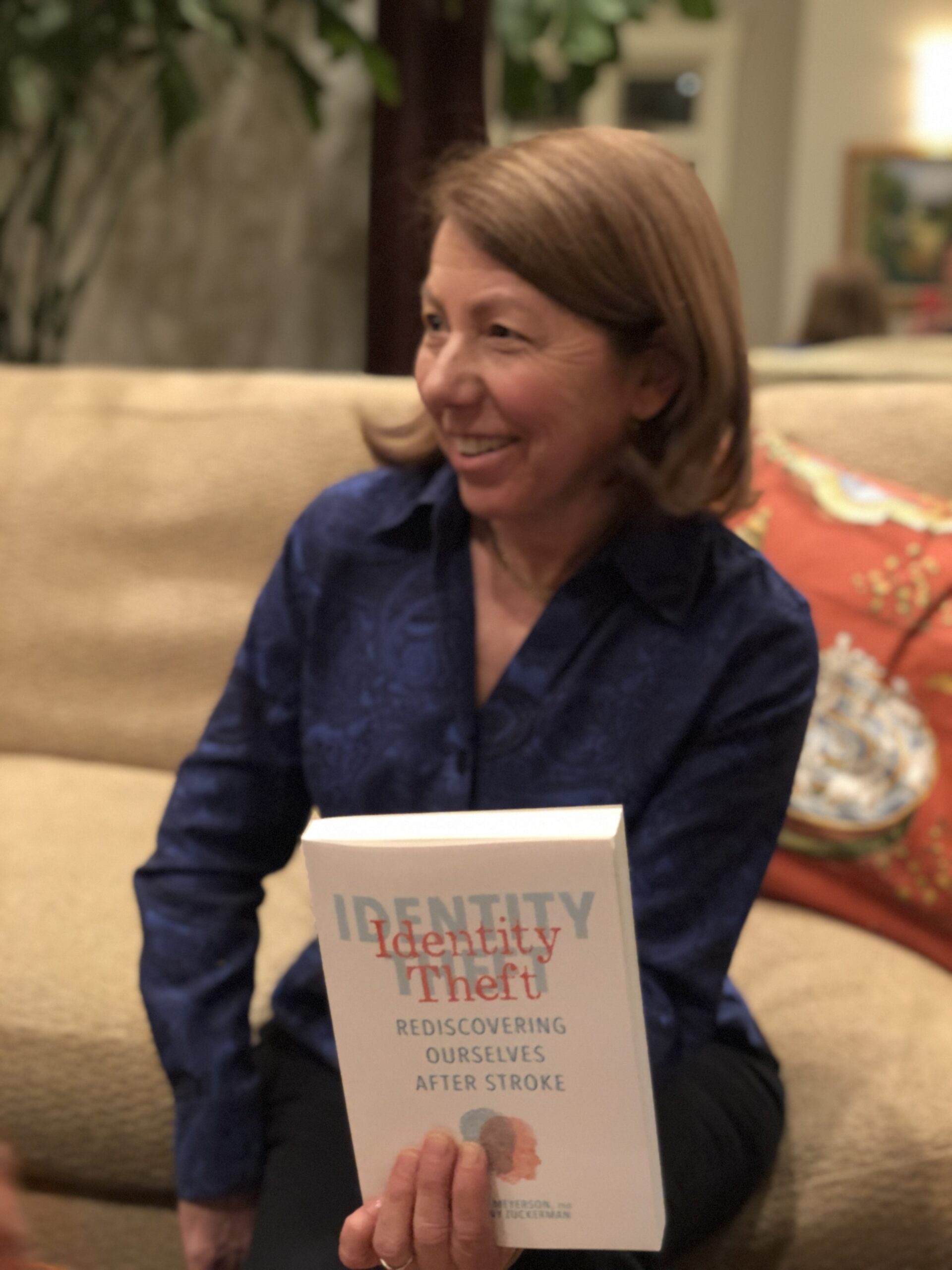

In response to that question, Debra took a deep dive into discovering her identity post stroke. What resulted was a memoir, aptly named Identity Theft, and a desire to see a change in the way stroke patients approach recovery – a way that includes equal focus on emotional health as physical health. On their website it states, “Recovery should also be about supporting a person to rebuild a happy and productive life, and a healthy sense of self, in the face of whatever capabilities can and cannot be regained.”

In response to that question, Debra took a deep dive into discovering her identity post stroke. What resulted was a memoir, aptly named Identity Theft, and a desire to see a change in the way stroke patients approach recovery – a way that includes equal focus on emotional health as physical health. On their website it states, “Recovery should also be about supporting a person to rebuild a happy and productive life, and a healthy sense of self, in the face of whatever capabilities can and cannot be regained.”

There are a lot of people in the world who have muddled their way through the prescribed recovery of the medical system and most of them have ideas of how it could be made better. But Debra, along with her husband, Steve Zuckerman, are taking those ideas one step further. By launching Stroke Onward, they are truly working towards change.

They know it is no small task – true change can take years, decades even. But in working to collaborate with a wider community and in creating and sharing new resources, change is possible.

I reached out to the team at Stroke Onward and Debra graciously agreed to answer some of my questions about her journey and Stroke Onward.

In your journey to discover your own identity post-stroke, what or who was your greatest source of support?

I wasn’t ready to explore that for three years – I was completely focused on rehabilitation and getting back to my old life, and my old identities. But when I lost my job at Stanford, that forced me to realize that may never happen. My husband, Steve, was super helpful. He’s so optimistic and always focused on “making the best of the situation”, so once I was willing to admit things needed to change, he was really supportive. For me, a lot of it was my background studying identity. There was also a group of colleagues at something called “The May Meaning Meeting”, which I went to four years after my stroke when I was thinking about writing a book. They were incredibly helpful in pushing me to think about the ways I could keep meaning and purpose in my life in the face of my disabilities. And other friends and family were supportive. I am really lucky I had (and have) a really strong support network. One of the reasons we created Stroke Onward is that we realized, as we interviewed people, that many wouldn’t find the path to rebuilding identity on their own – so more resources are needed.

What types of care would you like to see integrated into the stroke recovery system to better help patients navigate their emotional recovery?

That’s what we’re trying to figure out through the work of Stroke Onward. We think it needs to include more mental health professionals who have some training about stroke and aphasia, and who are focused on serving stroke survivors. And also, the system should embrace those services as normal practice, even if there is no specific diagnosis for an emotional disorder like depression or anxiety. Every survivor (and their families) need help to navigate this journey.

As a parent, we have a responsibility to ensure the emotional well-being of our children in the aftermath of any sort of trauma. Have you witnessed a need for family–based resources and/or is this something Stroke Onward is working on?

Absolutely. As we say often, every person is different, every stroke is different, and every recovery is different. But we firmly believe stroke is a family illness, and many family members could really use help navigating this change. This fits into the broader issue of the need for more attention to mental health – emotional fitness – built into our healthcare system. We don’t expect people to figure out their own recovery to a broken arm, so why should we expect them to figure out how to recover from a significant break in life as they know it?

The long-term effects of a stroke vary widely between patients. How do you ensure Stroke Onward is relevant for all?

Great question. First and foremost, we have to consistently acknowledge and emphasize that everyone’s journey is different and everyone’s needs are different. Our hope is to create a portfolio of resources that may have relevance to everyone and share them in ways that everyone can access them regardless of their location or financial resources.

If someone is in the midst of recovery and looking to work on finding themselves again, where’s a good place to start?

The flip answer is to read or listen to Identity Theft and visit the Stroke Onward website. More seriously, we wish we had more specific resources to share, but there just aren’t that many. We do plan to add a section to our website to share those we find that are specific to the emotional journey in recovery and rebuilding identity, whether initially created for stroke survivors or otherwise. And just one specific thought – really think about what is most important to you. Not roles, jobs, titles, or specific activities, but what ABOUT those things that really give you meaning, purpose and pleasure. That can be a great starting point for reaffirming, or redefining, your identities, and looking for ways you can include them in your lives, whatever physical and speaking abilities you do or don’t have.